Fireside Friday, February 6, 2026 (On Ancient Migrations)

Feb. 6th, 2026 07:13 pmHey folks, Fireside this week! I have ended up a bit behind in my work and as always it is the blog that much suffer first. In this case, we have in two weeks twice managed to have snow which only increased my workload (it didn’t cancel any of my classes, but did require me to offer a bunch of makeup quizzes and complicate daycare solutions). So we’re doing a fireside – next week we’ll be looking at a primer of the strategies of the weakest groups to take on the state: protest, terrorism and insurgency.

For this week’s musing I want to circle back to a topic that was part of our primer on the Late Bronze Age Collapse and that is population movement, migration, mergers and replacement. One of the elements of the public’s imagination of the past that is the most stubborn is the tendency to assume incorrectly that migration always means population replacement. In fact, the question is a lot more complex than that. Fortunately we’ve developed quite a few historical tools to try to tell what kind of population change is happening in any given moment of mass migration. Unfortunately, a lot of folks continue to hold doggedly to the notion that population migration always means extermination and replacement, some because they refuse to accept that anything they learned in their high school textbook in the 1960s might have been wrong (a perennial problem doing public education – the ‘history shouldn’t change’ crowd) and others because their ideology (usually some form of ‘scientific’ racism, thinly veiled) demands it.

You will tend to find this view – that population migration always means replacement – very often in older (19th century) scholarship, for a few reasons. One of those reasons is, and you’ll have to pardon me, simply the racist mindset: 19th century racists tended to view ethnic groups as fully self-contained population units, with genetic and cultural identities being nearly perfectly co-extensive, which pushed each other around rather than ‘fuzzing’ into each other on the edges. It is not hard to see, on the one hand, why scholars from societies that were at once engaged in nationalistic projects predicated on the idea that the genetic nation, cultural nation and nation-state are and ought to be co-extensive (e.g. the idea that all cultural Germans are also genetically related and that as a result they ought to be contained in a single German state) and operating racially exclusive imperial regimes overseas might be wedded to this vision. Indeed, their racially exclusive imperial regimes almost require such an (inaccurate) vision of humanity, so as to justify why ‘the French’ could act as a single, coherent body to rule over ‘the natives’ in a system that admits no edge-cases.1

Given that mindset – the assumption that ‘superior races’ must dominate, conquer and either enslave or replace ‘inferior races’ – it is not shocking that these scholars tended to assume, any time they could detect a hint of population movement, that what was happening was extermination and replacement.

That said over time we’ve developed better historical tools to allow us to question those assumptions. For the earliest 19th century scholars, all they had were the raw textual evidence. And that’s tricky because ancient writers routinely describe places and peoples as being utterly, completely and entirely destroyed – verdicts carelessly accepted by readers both 19th century and contemporary – when the actual destruction was very clearly less total. Students of Roman history will have in their heads, for instance, that in 146 BC Carthage and Corinth were utterly, completely and entirely destroyed and that Numantia was similarly annihilated in 133.

Except they weren’t. Corinth is, after all, still around for St. Paul to write letters to the Corinthians in the first century AD and it is still a distinctively Greek settlement, not some Roman colony. Carthage is recolonized by the Romans in 44 BC, but the people from Carthage continue to represent themselves as Phoenician or Levantine, suggesting quite a lot of the population remained Punic. Most notable here, of course, is the emperor Septimius Severus, who was from that reestablished Carthage, who is represented in our sources (and seemingly represented himself) as of mixed Italian-Punic heritage, with branches of his family living in Syria as locals. Evidently the Carthaginians weren’t all destroyed after all.

As for Numantia, Numantia was the most important town of the Arevaci (a Celtiberian people) when it was supposedly annihilated. Except Strabo, writing in the early first century AD notes the presence of the Arevaci civitas (that is, their legally recognized local self-governing unit) and lists Numantia as one of their chief towns (Strabo 3.4.13). Pliny the Elder (HN 3.3.18-19) writing in the mid-first century AD likewise notes Numantia as a major town of the Arevaci civitas, as does Ptolemy (the geographer) writing c. 150 (2.5). Numantia remains a continously inhabited site well into the late Roman period!

In short, many students and scholars are swift to accept declarations by our sources that a given people was ‘wiped out’ or annihilated or replaced when it is clear that what we are reading is intense hyperbole meant to stress that these people were badly brutalized (but not wiped out).

Alas, the first real tool we got to assess population movement reinforced rather than discouraged the 19th century ‘all replacement, all the time’ view: linguistics. After all, if your sources say there was a population migration and the local language changes, well chances are you really do have a lot of people moving. But assuming replacement here is extremely tricky because the thing about languages is that people learn them. One need only briefly look at a list of languages under threat today to see how people will migrate towards more useful or popular languages – abandoning local ones – even in the absence of official repression and indeed sometimes in the presence of active state efforts to sustain local languages. But it was easy for a lot of older scholars who already had a migration-and-replacement mental model to point, as we began to puzzle out the relations between languages, to languages moving and expanding and assume that the reason one language replaced another in a region is that the former language’s speakers moved in, killed everyone else and set up shop. The fact that locally dominant languages tended to become universal over a few generations could be taken as (false) confirmation of a replacement narrative.

What begins to lead scholars to question many (though not all!) of these ‘replacements’ was not ‘wokeness’ but rather archaeology, which offered a way of tracking the presence of cultural signifiers other than language. One example of this, noted by Simon James in The Atlantic Celts (1999) is population movement into Britain during the Iron Age. Older scholars, noting that Britain was full of Celtic-Language speakers (even more so before the Anglo-Saxons showed up, of course), had imagined (in addition to Bronze Age or very early Iron Age migrations) an effective invasion of the isles by continental Celtic-Language speakers (read: Gauls with La Tène material culture). But the archaeology revealed that burial customs do not shift to resemble continental burial customs – had there been a great wave of invaders, they would have brought their distinctive elite warrior burials and grave goods with them and they didn’t. Instead, the evidence we have is for significant human mobility and trade over the channel between two culturally similar yet distinct groups which remain distinct through the mid-to-late Iron Age (and beyond).

Archaeological data thus lets us see cultural continuity and regional distinctiveness even in cases where people are adopting new languages. It also lets us see more clearly people below the level of the ruling class (who tend to write all of our sources and mostly write about themselves). That in many cases lets us see situations where we know there has been an invasion or mass migration, even potentially involving sources attesting leadership changes or shifting languages, but where material culture shows no major discontinuity, suggesting that what has happened is a relatively thin layering of a new elite overtop of a society that demographically has not changed much among the peasantry (the Norman conquest of England is a decent example of this, as is the Macedonian conquest of the Persian Empire). Sometimes the common-folk material culture will then drift more slowly but steadily towards the material culture of the new elite, sometimes such a slow-and-steady drift (often involving the new elite drifting as well!) suggests broad population continuity, adapting to new fashions.

Of course the newest and latest tool now available are genetic studies. This is an extremely powerful tool which can in some cases remove (or add) key question-marks in our understanding. Genetic evidence has, for instance, offered some significant insight into the arrival of western Steppe and Caucasus peoples – the Indo-European Language speakers – into Europe. Notably, a significant amount of Early European Farmer (that is, pre-Indo-European-speaker migration peoples) DNA remains in modern European populations. Unsurprisingly, it is strongest in places like Italy and Iberia (where we have pre-Indo-European languages that survived), but it is a significant layer over most of Europe, telling us quite clearly that the pre-existing population was not entirely wiped out by the arrival of the speakers of a new language family (although the incoming ancestry groups to come to predominate, suggesting some degree of replacement).

Likewise a recent study of roughly 200 remains at sites generally identified as Phoenician surprisingly identified a remarkable array of different potential origins, with individuals from Sicily and the Aegean as well as North Africa and surprisingly few individuals apparently from the Levant, suggesting that quite a lot of the population involved in Phoenician colonization was drawn from a relatively wide range of places in the Mediterranean.

That said, I think it is also necessary to handle this sort of genetic evidence with care. There is, I think, an unfortunate knee-jerk tendency particularly among the interested public to treat genetic studies as ultimately dispositive, in no small part because people operate from the same flawed assumption as those old 19th century racists, that genetic communities of ancestry and cultural communities are and must be co-extensive, when often are not. But the Phoenician example above points to the problems there: whatever the original source of the genetic material among the Carthaginians, we know quite clearly from archaeology, literary sources, inscriptions and linguistic evidence that the Carthaginians regarded themselves as culturally linked to the Levant (not the Aegean) with close ties to the ‘mother city’ of Tyre. They adopted and maintained a distinctively Phoenician material culture identity even in the distant Western Mediterranean, gave their children distinctively Punic names, and so on.

All of that serves as a reminder that – again, contrary to what the racial essentialists (sadly resurgent in online spaces) would suppose – that genetic identity was hardly the only category that mattered to people in the past. Indeed, in a very real sense, genetic identity in the way we are testing it didn’t matter to those people at all. Given the genetic mix we see, there almost certainly were a meaningful number of people in pre-Roman Etruria who, by whatever quirk of luck had few or even none of the genetic markers we use to identify Early European Farmer ancestry – there’s plenty enough blending in ancient Italian populations for it. Yet those would have spoken Etruscan, followed Etruscan customs, held citizenship in an Etruscan polity, they would have been Etruscan in every way they knew that mattered to them. That their genetically significant ancestors were all actually descendants of early Indo-European speakers is something they would not know.

Genetic evidence thus comes with a risk of over-reading a simple answer to the complex question of people in the past who often had complex, layered identities, which they expressed in any number of ways.

Now I should note here at the end that I have pushed here against the assumption that migrations and movements always meant extermination and replacement. Indeed, it is far more often that we see – often quite violently, to be clear (but not always so) – populations blend to a substantial degree. At the same time obviously sometimes peoples really did push or wipe out pre-existing populations. The aforementioned Early European Farmers – the first wave of farming peoples entering Europe, coming from Anatolia, do seem to have largely displaced almost all of the pre-existing European hunter-gatherer population. Of course living in the United States, the arrival of European settlers resulted in a catastrophic decline of the Native American population, primarily from disease and also from warfare and displacement.

The point here is not a pollyannish assertion that historical population contacts were always peaceful (or the equally silly proposition that they were always peaceful except for European imperialism). The point is instead that these contacts were complex: incoming migrations did not always or even usually mass-replace existing populations. They very frequently blended, sometimes relatively more peacefully, sometimes very violently. Meanwhile there was also a lot of human mobility that didn’t involve mass migration or warfare at all, resulting in the nice neat ethnic lines imagined by earlier scholars rapidly turning into a blur with strongly blended edges all around.

Of course in many cases, the folks who remain intensely wedded to a pure extermination-and-replacement model of population interaction remain so wedded not because that model is true or comports to the evidence (of which they generally have little knowledge), but because it is ideologically necessary: they’re bigots who want to engage in ethnic cleansing (or want to ward off the idea their own ancestors might have been guilty of it) and so want to assert that population interactions must always be so, because if it is always so, if there is no other way, then they can no longer be blamed for their fantasies.

But it was not always so. History is complex and defined by human choices. Better things were possible and better things are now possible. Sometimes we even chose those better things.

On to Recommendations:

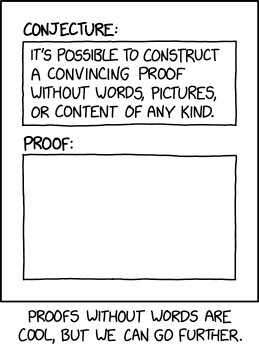

I’ve run across quite a few neat videos and podcasts over the past week. Over on ToldInStone’s podcast channel, he interviewed Roel Konijnendijk on Alexander the Great in a wonderfully informative discussion. I particularly like Konijnendijk’s stress on just how relatively limited the sources are here and how much we have to rely on conjecture to understand the process by which the Macedonian army emerged, how Alexander won his victories and how the Achaemenid army worked. These are informed conjectures, we do have evidence, but as always with ancient history, the evidence has frustrating gaps and limitations that need to be acknowledged.

Another great podcast that was recommended to me is Build Like a Roman, consisting of short episodes (around 20 minutes) talking the materials and methods by which the Romans built their famous structures. The podcast, by Darren McLean is just getting started laying out the different materials – concrete, lime, tuff, travertine, etc. – that were used in construction and is well worth a listen if you are interested in Roman building.

Meanwhile in naval history on Drachinifel’s channel, he has a long video (well, long by normal standards, regular length by Drach standards) on the start of Britain’s anti-slavery campaign at sea, led by the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron, which had the responsibility of enforcing Britain’s efforts to block the slave trade. The British ban on slave trading, passed in 1807, did not self-enforce, after all: British slavers arranged to fly false flags or get false papers from other countries in order to continue the trade illegally and of course the ships of other powers continued the trade. Drach takes this effort to 1820 and I hope he continues the series since the West Africa Squadron remained active into the 1860s.

Finally over on his History Does You substack, the admirably named Secretary of Defense Rock penned an interesting essay, “There is No Such Thing as Grand Strategy” which I think is worth reading. The title is in some sense misleading: sodrock immediately concedes that, by its narrow definition states do actually do grand strategy – that is, correlating economic, demographic, military and diplomatic policy to clear ends. What he disputes is the notion of some airy realm of pure strategy, where all of the messiness of politics falls away and states think purely in these terms. And that point is, I think, valuable. One of the challenges I’ve had in making my own arguments about Roman strategy is dealing with colleagues whose vision of strategy is so informed by the non-existent idea of this ‘higher plane’ of strategic thinking that they cannot recognize real strategy making – messy, ad hoc, temporary and complicated – when they see it.

Finally, on to this week’s Book Review. This week, I want to recommend Lucian Staiano-Daniels’ The War People: A Social History of Common Soldiers during the Era of the Thirty Years War (2024). Two quick caveats: first, I was given a copy of the book by the author (but I do not recommend every book I am given by an author and folks who send me books know that) and second, this is a volume that is a bit more pricey than what I normally recommend and I was going to hold off recommending it on that basis (the book is good, obviously) except that it has a much more reasonably priced Kindle version. I do generally try to avoid recommending academic books no one can afford, so the more affordable E-book is welcome.

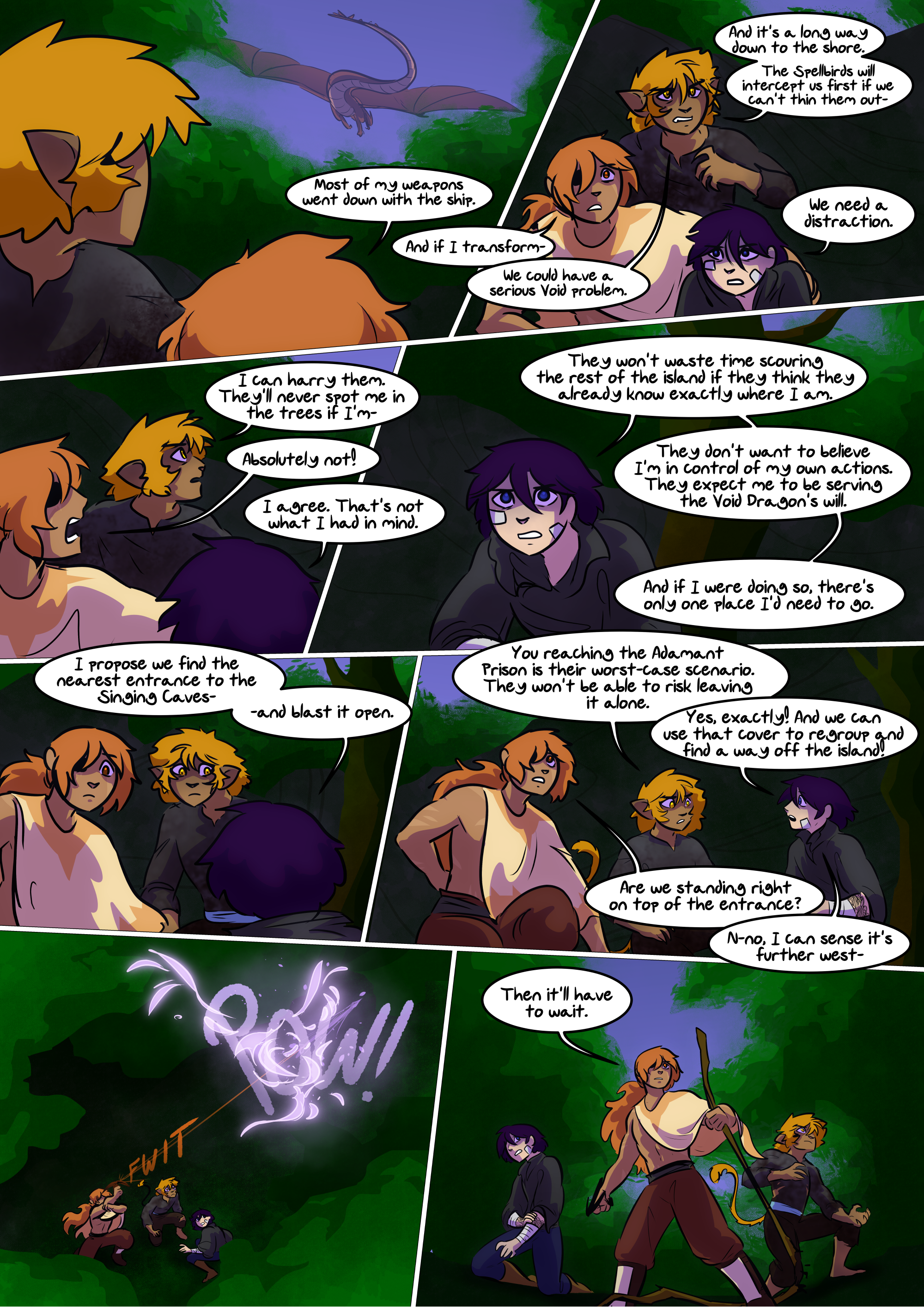

The War People fits into a larger genre we call ‘micro-history:’ rather than grand narrative of a whole war or reign or country, it is a focused history of a relatively small group of people, with the aim of illuminating what it was like to live a certain kind of life in a certain place at a certain time. In this case, the focus of the book is on the Mansfield Regiment, raised by Wolfgang von Mansfield, a Saxon noble, in Saxony in 1625 to fight in Northern Italy on behalf of Spain as part of the Valtellina War, a side theater of the larger Thirty Years War (and the Eighty Years War) fought over a key component of the Spanish Road which connected Habsburg logistics from Spain to the Spanish Netherlands overland. Doubtless that sentence made your head spin a little but for the reader as much as for the soldiers raised the actual politics of all of this is secondary (as Staiano-Daniels notes, when their war ends in victory, the regiment doesn’t even record this in their records): this book isn’t about the Valtellina War, it is about what it was like to serve in a regiment in Europe during this period.

In order to do that Staiano-Daniels uses the records and letters of this one regiment to dig into what life and military culture were like. How, for instance, the soldiery had their own sense of honor and appropriate action, which differed quite a lot from the civilians around them (one soldier writes, “to make it in this thing, you’ve really got to be young, and you’ve got to look at others with your fists” which is just remarkably on the nose), how they got into trouble, how they were (sometimes not) paid, what their diverse origins were, how they displayed their status (with colorful outfits made of cloth that they bought, traded and sometimes stole) and most of all the social values of this society. The result is a window into another cultural world, at once familiar and alien. Eventually, for lack of pay, the regiment effectively collapses – the perennial problem that states in this period had the resources and administration to raise large armies, but not to sustain them – with some portion of the regiment bleeding away and the rest pulled into a new regiment under the command of Alwig von Sulz.

The War People is well- and clearly-written, though I should be clear that it is written in a clear and effective but relatively dry academic style. The background politics and strategic considerations which motivated the raising of the Mansfield Regiment may confuse a reader, but they are also in a way fundamentally unimportant to the purpose of the book – what mattered was there there were many such regiments engaged in many such wars and this is how they (or some of them) lived. And that part of the narrative, with Staiano-Daniels presents as a mix of vignettes (like the theft and distribution of quite a bit of cloth, for instance) and careful analysis (like the study of how and how much soldiers were paid) very clearly and effectively. The micro-history focus is particularly valuable here: it is one thing to read in larger scale histories of warfare in Europe in this period, for instance, that states often struggled to pay their armies, but it is informative in a different way to read through the process by which the Mansfield regiment steadily withered away (pillaging not a few locals in the process) as its officers struggled to maintain it or manage its transition to a new formation without proper pay. That is the great virtue of this approach: it takes a general feature and then reveals how that feature manifested ‘on the ground’ as it were.

Consequently, I can imagine this book as remarkably valuable in the hands of at least three kinds of readers. For the scholar of the period, it is an effective, often penetrating work of social and military history, of course. But equally for the enthusiast or reenactor, it gives a real sense of what daily life was like in these regiments, including some very intense ugliness (there’s quite a lot of violence in this book, recorded through legal proceedings and such), but also the soldier’s own sense of who they were, what their values were and what sort of person could be upright in their company. Finally, for the world-builders out there who want to tell stories about early professional armies, the book provides an opportunity to ground those stories in the real experiences of soldiers in such a regiment and the many, many other people (women attached to the men of the regiment, civilians unfortunate enough to be near it) it impacted. Here the ‘on the ground’ focus of the book is going to be particularly useful in translating general ideas into a specific sense of how those ideas might translate to actual practice .